Why developers stopped asking permission to use feature flags

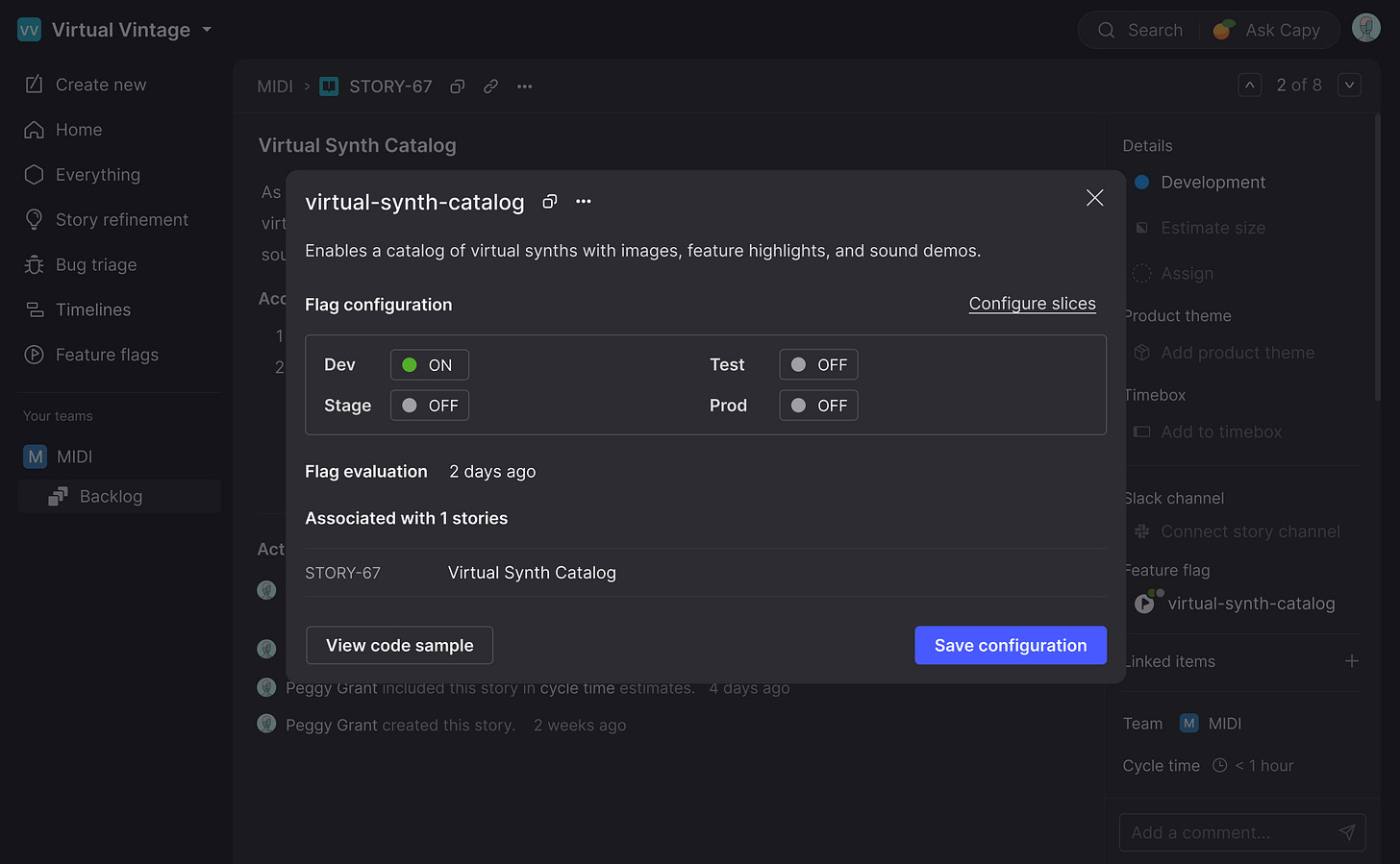

When flags live in the story, developers take control.

We interviewed eight developers about their experience with feature flags—both in previous tools and now in Atono—to understand how different approaches affect development workflows. What we discovered wasn't about technical capabilities, but about something more fundamental.

The most revealing moment in our research wasn't about features. It was about friction.

Dylan, one of our senior developers, described his experience at a previous company: "When you've got multiple systems for these things, it was harder to convince PMs when there wasn't a feature flag for a story. There was always reluctance to create a new feature flag because they proliferate through the codebase and never go away."

Then he contrasted it with Atono: "When feature flags are in the same system, it makes more sense to do it the more powerful way. I can be more trusting that it will eventually go away."

That shift—from asking permission to autonomy in making decisions—reveals something fundamental about how tool design shapes team behavior. When we embedded feature flags directly into stories instead of managing them in separate systems, we accidentally eliminated a bureaucratic bottleneck that most teams don't even realize they have.

The hidden cost of separated systems

Feature flags aren't new. Most development teams understand their value for safer deployments and gradual rollouts. But implementation often gets derailed by organizational friction.

In traditional setups, feature flags live in dedicated services like LaunchDarkly or Split. Someone has to provision them, configure permissions, and manage lifecycle. These tools also come with expensive licenses, which usually means only a few people in the company can toggle flags—adding another layer of access restrictions. Creating a flag becomes a decision that requires justification, coordination, and follow-up.

Over time, this can lead developers to avoid the overhead by shipping features the old way—bigger releases, more risk, less experimentation.

Mark Henzi, our VP of Engineering, put it simply: "Before Atono, we didn't really use feature flags at all. Now we do it by default—it gives us the confidence to move faster without worrying about users." That shift—from hesitation to habit—is what happens when flagging stops feeling like a heavyweight process.

It changed from a system of asking permission to one of trust. That subtle shift encouraged developers to move faster, take initiative, and experiment more freely.

How embedded flags empower developers

Embedding flags directly in stories wasn't just about convenience—it fundamentally changed how our developers approach feature development and gave them unprecedented control over their work.

Sandra described the practical empowerment: "It's really nice when I'm working on something new that can't get released yet—I just throw in a feature flag and go straight into Atono to turn it on and off. It beats having to change an environment variable."

But Lex identified the deeper confidence shift: "It makes it easier for me to think about the features I'm developing. I just think, 'oh, it's all behind a feature flag. It's okay.' I can be more trusting that it will eventually go away."

This isn't about technical capability. It's about developer autonomy at the moment they structure their work. When flags are integrated with stories, developers gain ownership over feature rollout decisions rather than depending on external gatekeepers.

The empowerment extends beyond individual confidence. Developers now approach feature development with the assumption they control the release timeline. They can experiment freely, knowing they have the power to enable features for themselves first, then gradually expand access as confidence grows. This sense of ownership transforms how they think about risk, testing, and iteration.

The broader pattern of developer empowerment

The feature flag insight revealed a broader principle about empowering development teams through tool design.

When workflows require switching between systems or asking permission from gatekeepers, developers naturally optimize for tool limitations rather than best practices. They avoid feature flags not because they don't understand their value, but because the bureaucratic overhead makes experimentation feel expensive and risky.

This pattern shows up with other development practices too. In many teams, developers skip writing comprehensive tests when testing tools are disconnected from development workflows. They avoid refactoring when tracking technical debt requires separate systems with their own approval processes. They compromise on thorough code review when it adds complex coordination steps to deployment pipelines.

The solution isn't cramming everything into one interface. It's identifying the moments where permission structures discourage good practices, then designing those bottlenecks away. When developers have direct control over feature flags within their normal workflow, they use them by default. When they have to ask someone else or switch systems, flags become an exception rather than standard practice.

It's not about having more features. It's about giving developers direct control over their tools and reducing friction between intention and action.

What this means for empowering development teams

This research changed how we think about feature development—specifically, how to design tools that empower rather than constrain developer decision-making.

Instead of asking "what features do teams need?" we started asking "what good practices do teams avoid because they require permission or coordination?" The answer shapes different design decisions around developer autonomy.

For feature flags, it meant embedding them in stories so any developer can create and control them without external approval. For acceptance criteria, it meant making them directly editable and linkable so developers can reference and update requirements without bureaucratic overhead. For team coordination, it meant connecting Slack discussions directly to stories so developers can initiate focused conversations without manual setup.

The pattern isn't about building comprehensive platforms that replace everything. It's about identifying the moments where permission structures discourage best practices, then giving developers direct control over those workflows.

When developers have the autonomy to use good practices without asking permission, those practices become habits rather than exceptions. When bureaucratic friction is removed and developers feel empowered to make technical decisions, development velocity increases in ways that are measurable and sustainable.

Ready to see how empowering developers with integrated feature flags changes your team's development practices?